I've also added pictures.

Samuel Weber, in his article War, Terrorism, and Spectacle, writes that after the fall of the Twin Towers, US citizens had to be urged to "start spending again," to "get back to consuming," and in many ways this economic reinvigoration has emerged as a consumption of the tragedy itself. United 93 (Paul Greengrass, 2006) is one such consumer product. The film tells the story of United Flight 93, the fourth plane hijacked on September 11th, 2001, and the only one in which passengers were able to overpower the terrorists, and crash the plane far from the intended target.

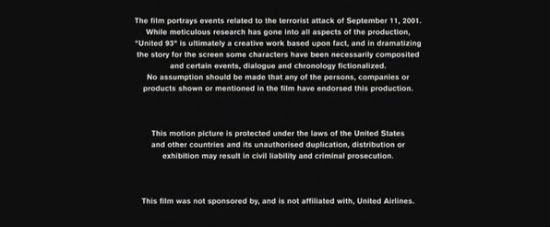

Feel free to judge the entire film based on this one image.

United 93 is imbued with "authenticity"; it is "a terse realistic depiction of ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances" (Žižek). In Slavoj Žižek's response to the film, he describes it as trying to be "as anti-Hollywood as possible": there are "no special effects, no grandiloquent heroic gestures" and "no glamorous stars" (except the post-2006 breakouts Olivia Thirlby (Juno, The Wackness, Bored to Death) and Cheyenne "Shy Action" Jackson (30 Rock)). The cinematography consists mainly of shaky hand-held camera-work. The set designers explicitly strived to capture the "feel" of 2001, with characters' hand-held technology as the prime indicator—doomed passengers tell their families they love them on old clamshell mobiles and airphones; a girl listens to a CD player; a woman comments on a fellow passenger's boxy laptop—"Is that the latest model?" Locations are captioned ("Northeast Air Defense Command Center, Rome, New York") as though they really are the places for which they are standing in. When the hijackings do finally occur, observers meet them less with panic than disbelief. Those reporting the hijacks have to repeatedly quell incredulity and questions of "Is this a sim?" with affirmations that no, "This is real world." These skeptical characters ask questions the audience would, so as characters are reassured, so, too, are viewers, of United 93's realism.

Shy Anne ain't shy on talent.

Žižek writes that this "avoiding of sensationalism," and "sober and restrained style"—this "touch of authenticity" should make viewers suspicious, as to "what ideological purposes it serves." But even more so, this meticulous authenticity and choice to present the movie as in "real-time"(a minute of screen-time is a minute of the viewer's time; no fades or ellipses) just makes the film boring. Whereas in a movie concerning fictional events, long stretches of mundanity could provide tension for what is to come, in United 93, even the least news-houndish of viewers already know what is going to happen. Greengrass's little attempts at foreshadowing—choosing to show an interminably long emergency exit demonstration instead of utilizing the only truncating editing device available (cutting to the just-as-dull military and airline control rooms)—and his efforts at creating tension, with furtive looks exchanged between the soon-to-be-terrorists, are rendered futile. These hijackers are presented not as a part of some incomprehensibly large and shady terrorist organization, but as "desperate and deranged individuals" (Weber), the violence they commit becoming a private matter. Thus as the terrorists are the only well-defined and therefore identifiable characters, the viewer comes to root for them, if just so that something will happen. This seems the reverse of the intended effect of any so patriotic a film, but could possibly be deliberate, so as to make the viewer feel ashamed of such thoughts, and therefore guilt-trip them into higher degrees of nationalism. But Greengrass, director of two of the Bourne films, does not merit the assumption of such subtle emotional prowess.

We may hate A-rabs, but we ain't no fuckin' racists.

Instead, as Weber writes, this seemingly-authentic spectacle allows the viewers to "identify with the ostensibly invulnerable perspective of the camera." The unavoidable, unanswerable question of who is filming these presented-as-real events only augments the camera's invincible position. Unlike television news media, in which subjects are very aware of the camera's existence within their space, United 93 is presented as though there is no one there filming it, and the viewer is voyeuristically watching these events occur right as they happen. The spectacle, and thus the spectator, is "at once here and elsewhere" (Weber). Elsewhere on United 93 as it is hijacked, but simultaneously here, in a theatre seat, safe to go home once the credits role, without the fatal ends of the actual passengers (there were no survivors, as told by a title card). The spectator thus feels triumphant, immortal. They have gone back in time and taken part in destroying these terrorists, and due to the obsessive degree of realism, they feel as though they know how this really happened (though in reality, there are no survivors to corroborate Greengrass's version of the events), and thus feel that they could easily deal with a hijacking themselves. This terrorism does not seem so unexpected anymore. All someone needs to quash it is enough confident, middle-class white male patriots to figure out a plan; just some hot water, knives, and forks—the available supplies on an everyday commercial flight.

Even extreme realism can't stand in for the truth. Thanks, credits!

Žižek asserts that with United 93, this disaster "turned into a kind of triumph" sustains the United State's need for "major catastrophe in order to resuscitate the spirit of communal solidarity." But even more so, this film (perhaps groundlessly) reestablishes that superior feeling destroyed when the Twin Towers were; that American idea that "it can't happen here." United 93 provides the United States with a post-9/11 update of that wholesome, very American mantra: "It can happen here, but we now know how to deal with it." A sign shown in the opening scenes of the film reads, "God bless America." And God bless America indeed, for with the false sense of security perpetuated by such cultural products as United 93, if ever a very real, non-privatized terror strikes, we are going to need all the benedictions we can get.

Notes:

-I realize the whole "privatized" terrorism argument is not very well developed, but if you'd read the articles we had to read, it kind of would be.

-Before accusing me of being heartless, I actually did tear up during the bit when people were calling their families. Though I did laugh when Shy Anne was all, "You believe me, don't you, Mom?"

-I've never seen the Bourne films but I'm assuming they're not "imbued" with much emotional depth. Matt Damon's been funny in 30 Rock, though, so I guess that's good, right?

-I also stopped watching LOST mid-way through season two, when they killed everybody I liked, so maybe new, even less bearable characters are introduced and I should give Kack some slack. But since I couldn't even get through the first couple of seasons even with the promise of Jeremy Davies come season five, I'm not sure even J.J. Abrams could come up with something so torturous.

-Then again, I've watched both Alias and Felicity… young Jeffrey Jacob really does have a talent for making his viewers want to stab out their corneas.

-Dude, but in LOST that one guy had a gun! So they could have just shot the terr'rists. But also they were flying from Australia, and even the smallest, least-notorious terrorist organizations are not that desperate.

-Also, the terr'rists were the only vaguely attractive actors in U93, so maybe I was a bit biased in my response.

Articles:

Slavoj Žižek, Five Years After: the Fire in the Minds of Men

Samuel Weber, War, terrorism, and spectacle: On Towers and Caves

No comments:

Post a Comment